Recommendations

The novel comprises eight stories about the people of the fictional kibbutz Jikhat. It describes their experiences, perspectives and looks at the different lives of the community.

We meet Zvi Provisor, the pessimistic gardener who only announces the saddest news from the newspaper, Martin van den Bergh, a shoemaker who survived the Holocaust and wants to teach Esperanto in the kibbutz, Mosche Jaschar, a schoolboy who is being brought up in the kibbutz, separated from his brother, because his mother has died and his father is seriously ill, and Joav Karni, who meets Nina, a young woman who does not want to go back to her husband under any circumstances, during his nightly rounds.

All the observations are written soberly, carefully and sensitively, and yet they describe fundamental and existential feelings. Amos Oz explains in a wonderful way why life weaves people together.

In this novel, the author attempts to retrace her own family history by visiting the places where her ancestors lived and worked.

Petrovskaya tells the story at breakneck speed, so that sometimes a single sentence stretches over several pages, from the beginning to the end of a chapter, without even a single thought being recorded. She follows memories, allusions and mentions down to the smallest detail, sometimes pictures, articles or historians find their way into her research, but mostly the author is alone with her thoughts, the disbelief in what happened and has happened. She plays with names, different languages and different ways of writing, blurring the boundaries between reality and fantasy. Nevertheless, she tries to capture reality, to feel it and to give free rein to her feelings.

We learn a lot about her family, aunts, great-grandmothers, brothers-in-law, sisters and the events of the story, yet distance and ignorance remain on both sides, because no one can, or is allowed to, or perhaps wants to, know everything.

It is nice to experience Petrovskaya's cautiousness, how carefully and yet consistently she tries to capture all the impressions. One word keeps tripping you up while reading: "deaf and dumb" is the term the author uses to define her ancestors and their pupils. In a way, it is misleading, because she describes the beauty and diversity of sign language, which makes deaf people deaf, but not mute.

In Vielleicht Esther, Katja Petrowskaja has succeeded in capturing and presenting the fragments and contradictions of the story without creating drama or dumbing it down.

Tel Aviv native Liat is spending a semester abroad in New York, where she is translating books into Hebrew. While working, she meets the Palestinian Chilmi in a café, who prefers to draw the sky and the sea. Liat doesn't really want to get to know him, and as a Jew she certainly doesn't want to start a relationship with him, but her feelings get the better of her. The two live a temporary love affair, hidden in the hustle and bustle of New York and always worried about being seen by acquaintances. When Liat returns to Israel, the two part ways painfully, as it is certain that they will not be able to meet again there. But the feelings of this scandalous love become too strong; Chlimi finally enters Israel illegally and searches for Liat - on the beach in Jaffa.

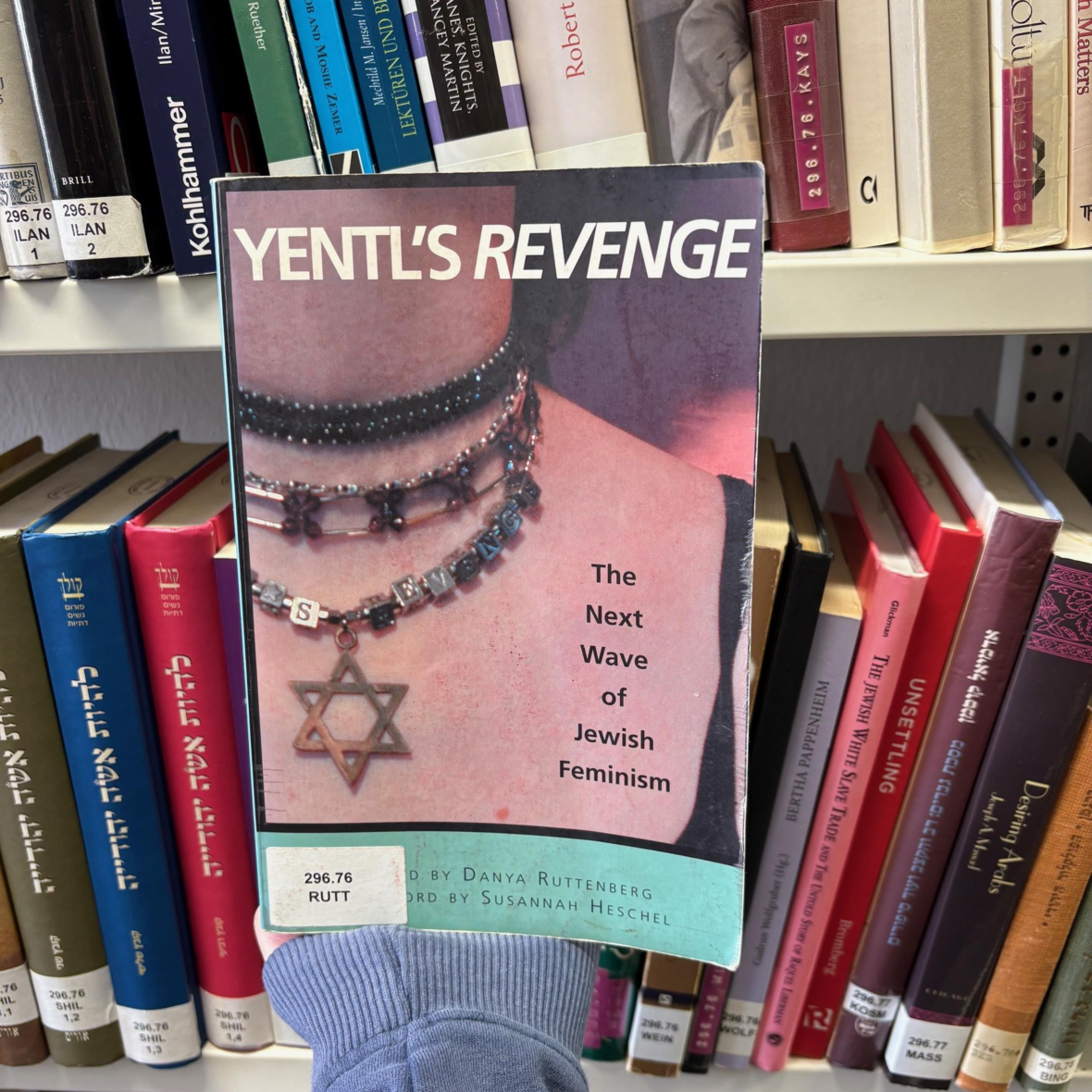

Yentl's Revenge

"Yentl's Revenge" is a heart-felt collection of essays filled with 20 womens' experiences, memories and belief-systems that center around their Jewish heritage and upbringing. It is a bitter-sweet homage to their roots, which shows how intertwined and at the same time often seemingly irreconcilable their religion and feminist ideals are. "Yentl's Revenge" makes you laugh out loud and feel respect for these remarkable women, who share their intimate stories in a witty, honest and often raw way, evoking the impression of an earnest talk with one's older sister.

One of the authors discusses the challenges of being a female rabbi, another speaks about empowering her daughter to wear tzizit and yet another author breaks her silence on the sexual abuse and incest she experienced at the hands of her Holocaust-survivor grandfather. From everyday trials readers will relate to, to hardships most of us can (hopefully) only imagine, this book is much more than a “revenge”, it is a call to challenge tradition, identity and religion as we know it.